Starting from June 19, 2020, the State Council consecutively approved four cities, Changchun (Jilin province), Chengdu (Sichuan province), Yantai (Shandong province) and Xingtai (Hebei province), to administratively convert surrounding rural counties into city districts, which means the former counties will be governed by their local cities.

Over the past ten years, China has converted a total of 141 counties and meanwhile added 110 city districts. As China’s urbanization trend continues, not only the countryside economy would be affected by urban economic forces that focus on infrastructure, construction and improvement of public service, but the rural life would be affected by urban influences.

As the consumption culture permeates areas that formerly relied upon agricultural subsistence, knowledge and experience in farming have decreased and become a rare skill. The lifestyle in rural China becomes a mixture of joy and woes.

Familiar, yet unknown

It was after school in the gathering twilight, an interval of time during which Qi Qi, a nearsighted eleven-year-old girl with thick-lensed glasses, could relax before supper. She stood on her pink Balance Bike and slid around the yard where five square meters of home-planted vegetables were planted.

“Even though I was born and grew up in countryside,” said QiQi, looking with a confused gaze at two similar-look green plants in Grandma’s front yard. “I barely can tell the difference between these two vegetables.”

Guo Wei, Qi Qi’s father, walked from the house and furrowed his brow at her confusion. He paused before picking a few sun ripened tomatoes for the meal already cooking within.

“They are eggplant and pumping seedlings,” Guo Wei responded. Throughout his childhood and teenage years, Guo spent most of his time assisting his mother on farm lands which are now rented out to a local herb planting and manufacturing firm. Guo left farming, to pursue selling ceramic tiles in a store as a more suitable way to support his family.

Qi Qi leaned closer to the two greens seedlings and took a good at the leaves. “Ah, pumping seedlings have curvy strings!” She happily reported to her father. “Look, there are more greens growing! Let me check them out…”

“You have to do your homework now,” Guo Wei stopped the child as she was about to sneak out of the yard to explore the natural world beyond. “Last night, you were up until 11p.m. Why can’t you finish the homework fast?”

It is true that Qi Qi has a propensity for procrastination, especially burgeoning load of daily homework issued by her school. She had successfully seized numerous moments to play and avoid homework throughout the first grade, a habit she has perfected now in fourth grade. As a result, her parents often sit beside her, enforcing her study time on a daily basis.

As Guo Wei requested a second time for her to do homework, Qi Qi reluctantly stepped off her Balance Bike and left the yard behind. As she dove into the boredom of working on several test papers, she couldn’t help diverting her thoughts back to the inviting yard and the two greens she just learned.

Soon, on the margin of the test paper, a beautiful portrayal of pumpkin seedlings sprouted forth with curvy sprigs and blossoming leaves.

Pressure to Move On

Like Qi Qi, many children and teenagers in the rural areas of China are loosing carefree time to competitive school study. Additionally, they have to attend tutoring classes to improve maths, Chinese or English after school and on weekends. Some even attend daily after-school classes if they have trouble accomplishing homework on their own. The tutoring fees for these classes range from 150 to 600 yuan per hour, depending on how effectively the classes can enhance the students’ exam scores.

Qi Qi’s cousin, Jin Wu, a sixteen-year-old teenager who was about to take High-school Entrance Examination within one week, had been taking tutoring class on maths at the cost of 360 yuan per hour.

“As long as he can enter the best-quality high school,” Jin Wu’s father said, “I am willing to pay the higher tutoring fee.” He was concerned because in the latest mock exam, Jin Wu was only rated entering a mid-level high school. It required an increase of seven scores to enter a better tier of schools.

When Jin had dinner with his family, not only his father, but his mother and grandparents would encourage him to study hard or give him special food treats. He barely responded beyond his thanks and quickly finished the meal to obediently return to study.

“There is no way that this new generation will ever return to doing farm work in the future,” Jin’s father says. “They know nothing about farming skills. Study is the only access to their survival.”

Purchasing the future

Both Qi Qi’s and Jin Wu’s parents bought apartments in town, about 14 kilometers away from their rural farm lands. They felt lucky they made the purchase decision early, otherwise they couldn’t have afforded it, since the price of residential land has dramatically surged over the past few years.

Since the 2016 G20 took place in China, the real estate market in Hangzhou and the surrounding areas of Zhejiang province has boosted. In 2018, the city had to adopt a housing lottery system in order to prevent a property bubble. Needy families can only purchase apartments with winning the lucky draw.

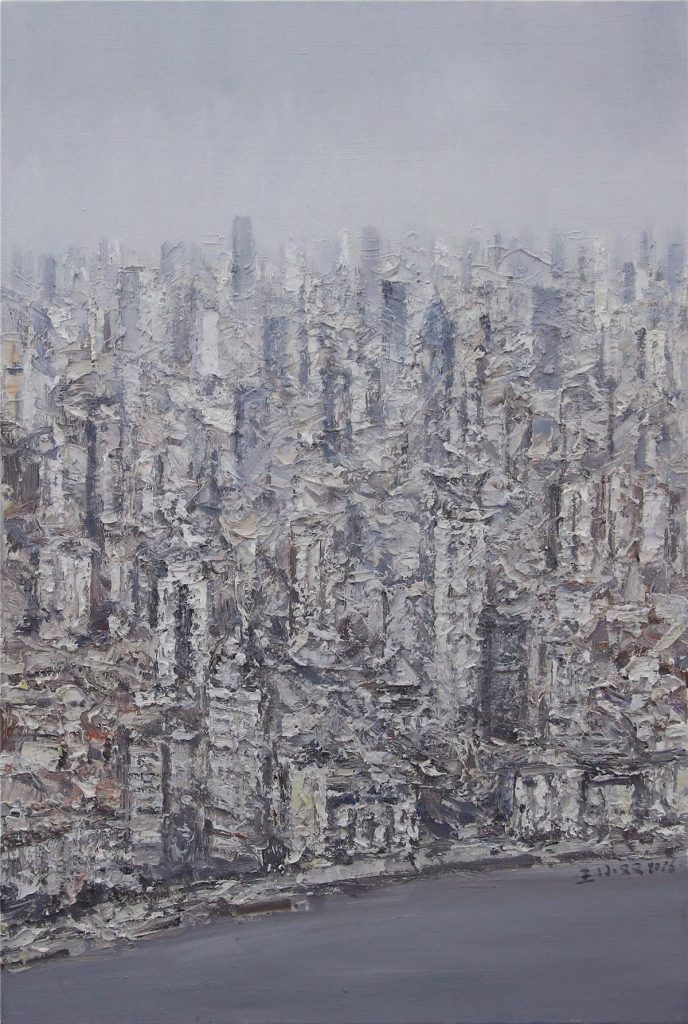

As many old residential complexes were dismantled, new high-rise residential buildings rapidly took their place. As exquisitely-designed as the ones in first-tier cities, these new apartments cost half or one-third of their urban counterparts.

“In my father’s generation, they built a three-store countryside villa on their farm property which will be the legacy for their offspring,” said Jianzhong Sun, a 42-year-old construction manager who lives in the same apartment complex as QiQi’s family. “But now, for the young generation like me, purchasing apartment in towns is a more rational decision for the future.”

At the price of RMB1.40 million (US$ 200,000 dollars), Sun bought a new apartment in 2019 in the suburban town of Xiaoshan, an administrative district of Hangzhou. The apartment is composed of two dinning rooms and four bedrooms, occupying 170 cubic meters, on the thirteen floor of an eighteen-floor high-rise.

Sun hopes to buy two more apartments as legacies for his two children in the near future. “Though my business seems profitable because of the the vast-scale of real estate development in China, it has become more competitive these days.” Sun added. He said his profit in the construction sector is down to 20% from 50% ten years ago.

“Nowadays, we spend money much faster than we earn,” Jia Wei, Sun’s brother-in-law and a window-maker, says, “Twenty years ago, I could only make 50 or 70 yuan per day. I felt fulfilled since I could accumulate a few thousand by the end of the year. But now, the money I made yesterday can be fully spent today, even though daily income increases to be hundreds per day.”

One week ago, Jia Wei purchased five automatic machines for his new plan for making windows, with a price tag of RMB150,000 (US$23,000). Adding the rental fee of workshop and salary of two workers, his overhead costs will exceed RMB300,000 annually.

“It is inevitable that automation will replace hand craftsmanship, ” Jia says, “I have been considering this plan for years. It took me a lot courage to enter this new game with its higher stakes.”

From Rural to Suburban China

On the way from QiQi’s grandmother’s farmstead to QiQi’s family apartment in town there is a famous real estate development program, known as the Forest and Sea. It occupies 204,000 square meters (5,000 acres), so far it is the biggest residential property in Hangzhou. It claims it will attract 100,000 residents to live there in the next ten years by providing full facilities and every urban convenience including hospitals, schools and supermarkets.

“It will soon become an ideal residence for people working in urban areas,” Guo Wei commented when he drove by the the Forest and Sea. “If the place is built as it claimed, then there would be no need for people to leave the place because it would have everything.”

At the back-seat of the car, Qi Qi leaned against the window. She looked out at the heavy equipment and the open scars where construction sites were being prepared. Then she opened her textbook and withdrew a pumpkin sprout she had pressed in the pages.