Chinese pavilions spark sentimental visions.

By Jude Jiang

Near the corner of a noisy intersection filled with downtown Shanghai’s endless stream of traffic in lies a pavilion. Painted with faded hues, from its sky-blue tiled rooftop to its burgundy wooden pillars, the hexagonal structure elegantly demonstrates serenity and harmony.

Chinese pavilions have long been a part of Oriental gardens and dotting the picturesque mountain tops. Ancient poets composed verses or leisurely discussed philosophy with lords and magistrates. Today, people may rarely find time for relaxation or waxing poetic. The pavilion, therefore, may get little use, apart from occasionally being used as an impromptu phone booth while someone stops to sit and make a private call on their mobile phone.

Though it has fallen into disuse by the busy city people, the pavilion lures other residents to its eaves. Stray cats seem drawn to this shelter and place it in practical usage to play, groom their fur, rally for a fight, eat the food kind-hearted aunties bring for them or just lay down and soak in the sunshine. Feral cats are cautious but they are willing to leave behind the security of the bushes and hedges to stroll across the open spaces to reach this enticing architecture.

While gleefully indulging in their feline pursuits under the sunshine around the pavilion, the cats remain vigilant. They raise their heads as one, and freeze. Taut muscles poised and ready to pounce, they listen cautiously, and upon hearing any sound of footsteps approaching or vehicle passing nearby, they scatter to the nearby bushes. However, some wise elders remain and intently monitor the activities from their 360 degree vantage within the structure.

Often passersby neither notice the cats nor enter the pavilion. They continue on in their quick pace to their own destination under the watchful gaze of the pavilion’s feline guardians. But the cats are blissfully unaware of the grand history of humble buildings like these.

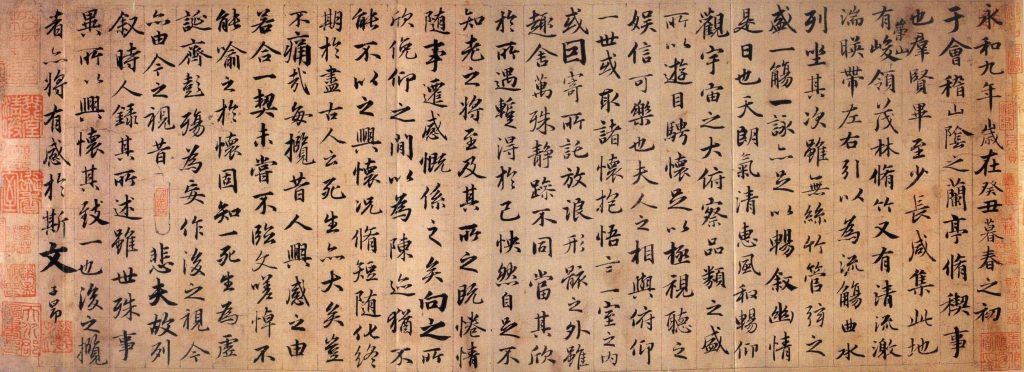

“Truly enjoyable it is sit to watch the immense universe above and the myriad things below, traveling over the entire landscape with our eyes and allowing our sentiments to roam about at will, thus exhausting the pleasures of the eye and the ear,” wrote Wang Xizhi, a renown Chinese calligrapher during Eastern Jin Dynasty (A.D. 353), in his famous essay, The Orchid Pavilion. In this verse, he extolled his sentiments to the view from the pavilion.

Is this not the very sentiment that attracts these stray cats? Wang Xizhi assembled with forty old and young illustrious scholars in the Orchid Pavilion where they chatted, sang, drank and relaxed. They also pondered philosophy.

Wang Xizhi mentioned that his pleasure not only came from viewing the mountains, trees, bamboos and streams from the pavilion, but also from noticing his companions,“unburden their thoughts in the intimacy of a room, and some, overcome by a sentiment, soar forth into a world beyond bodily realities.”

Though there was no traffic noise in that age to disrupt their fraternity within the pavilion. After the ripple of pleasures triggered by the view from the Orchid Pavilion, Wang found himself in a sad mood contemplating the limited space inside with the immense wilderness outside the pavilion. This image caused him to compare humans’ limited lifespan with infinity of the Universe.

“Although our lives may be long or short, eventually we all end in nothingness. ‘Great indeed are life and death,’ said the ancients. Ah! What sadness!” Wang Xizhi surmised at the end of his essay.

Modern architects employ cubic windows in their stark and impregnable concrete and steel behemoths made for residential, shopping and working spaces. When the buildings provide more internal space and security, do they also restrict our sentimental outlook?

Today one third of world’s high-rise buildings above 150 meters in height are located in mainland China. Thus, seeing a grand view through panes of high-rise building window is an ubiquitous experience, while discovering such grandeur in the windowless view from a pavilion on a mountain has become a luxury.